Christopher Buckley (Ed.): Review by Maggie Paul

Christopher Buckley (Ed.), Naming the Lost: The Fresno Poets, Interviews & Essays (Stephen F. Austin State University Press)

Naming the Lost: The Fresno Poets, edited by Christopher Buckley, is a comprehensive and engaging collection of interviews, essays, biography, and personal anecdotes of the thirty-four poets who energized the California poetry scene from the early 1960s to the 1980s in the “Dust and Wind State” of Fresno, California. It is an act of preservation and a tribute to those who serendipitously crossed paths and created their own detectable poetic style while studying and/or teaching at Fresno State College in the San Joaquin Valley. The purpose of this collection is aptly set forth in the book’s epigraph by Phil Levine: “I believe the truth is we form a family with other poets, living and dead, or we risk going nowhere.” Each poet in this community of writers is acknowledged for their noteworthy contributions toward a poetics that grew out of the Central Valley of California during the turbulent 1960s and firmly took hold nationally as poetry itself began to address the working class experience. It is a movement that could only have come from that time and place. While one third of these poets have now passed on, this volume brings the community together for readers to experience again.

Fresno is a major city in the San Joaquin Valley of California surrounded by agriculture. Far from urban San Francisco and Los Angeles, in the late 50s and 60s it was anything but a mecca of art or culture. So, why Fresno, a landscape of fig and apricot orchards, grapes and raisins, cotton, alfalfa, citrus, peaches, plums, nectarines, almonds, tomatoes, and more? One has to explore this journey beginning with the poet Phil Levine. Levine interviewed for a teaching job at Fresno State University in 1958 because his son suffered from asthma and the dry climate was recommended for his health. (This brings to mind the poet Adrienne Rich who in the 1980s moved from the east coast to the Mediterranean climate of Santa Cruz, CA on the advise of her doctor; she suffered from arthritis.) David St. John’s grandfather, Dean of the Humanities and Chair of the English Dept. at the time, hired Levine. Soon after, some of those who would later become integral to this group of Fresno poets moved out to work with Levine from elsewhere: Peter Everwine in 1962 to help develop a creative writing program, and Chuck Hanzlicek in 1966 to join in that program. Poets Larry Levis, Gary Soto, and many others were natives of the region. While the Beat poets left New York’s Greenwich Village for San Francisco and began gathering at Ferlinghetti’s City Lights Bookstore, the Fresno poets, under Levine’s tutelage, proved to be a poetic force of the their own.

Buckley’s book preserves the voices of the poets talking about their own work and the work of their comrades; we get inside views of their processes, struggles, and approaches to poetry that begin, as Mark Jarman notes, to address class consciousness, surreal imagery, and intricate narratives. We learn that Larry Levis was excluded from attending Berkeley and any of the UC campuses because he’d earned a D in photography. “How lucky I was,” he says in The Condition of the Spirit, “though my little destiny was completely disguised as failure, for at Fresno State I would spend the next four years in Levine’s poetry workshops, although I could not have known that then. No one knew anything then. It was 1964.” Gary Soto and Juan Felipe Hererra, both sons of migrant farmers, also describe their experiences at Fresno State with Levine: Soto as a student, and Hererra as a teacher.

Naming the Lost draws upon earlier collections that focus on Fresno poets and the power of place such as Piecework, 19 Fresno Poets (1987), How Much Earth (2001), The Geography of Home: California’s Poetry of Place (1999), The Condition of the Spirit (20024), Bear Flag Republic: Prose Poems and Poetics from California, (2008), as well as books that are homages to Phil Levine, Larry Levis, and Weldon Kees. It is rife with anecdotes that one by one develop the story of how Fresno came to be an epicenter of modern American poetry. One such anecdote comes from James Baloian, an Armenian-American poet born in the San Joaquin Valley. Boloian recalls how, in the first class he ever took with Levine, the instructor weeded out the student body from thirty to ten: “Writing poetry is my life,” Levine said, “and I expect my students to embrace this attitude or leave.” The remaining students, including Larry Levis, Luis Omar Salinas, Sherley Anne Williams, and Robert L. Jones, became part of what later was known as the first generation of Fresno Poets. In the 2013 publication Coming Close: Forty Essays on Philip Levine, David St. John contends that “…there is a clear consensus that there simply was not and is not any more passionate, wise, hilarious, useful, fearsome, brilliant, loyal, or inspiring teacher of poetry, as literature and craft, as Philip Levine.” Naming the Lost offers numerous windows into the experiences of these accomplished poets. Levine’s influence echoes throughout; each poet has their own personal take on how his teaching and modeling of the art has affected their own practice and pursuit of poetry.

The turbulent era of the 1960s, which redefined America and called into question its values, influenced the poetry and lives of each of these poets; national and international events became central to their work, as many of them participated in marches, rallies, and evocative readings calling for a re-evaluation of America’s conscience. Another sign of the times reveals the conspicuous absence of female voices in this group of poets, as only eight of the 34 poets included here are women. It would be 1973 before the women’s movement shone light on the overlooked talents of many female writers. But the women who did come up with the Fresno poets and who are present in this volume include Sherley Anne Williams, Roberta Spear, Suzanne Lummis, Sandra Hoben, Jean Janzen, Kathy Fagan, Corrinne Clegg Hales, and Dixie Salazar.

This comprehensive collection of essays, interviews, and biographical material offers readers a three-fold entry into the personal and professional lives of the Fresno poets—their friendships and individual approaches to a new poetics that reflects a California sensibility undocumented and undeveloped until the early 1960s. The book is rife with history—the history of the San Joaquin Valley as seen through the lens of poetry. It is not the CA of Hollywood, surfing, or the Haight-Ashbury. This California rises out of the hard earth of agriculture, migrant farm-workers, and the working class; its residents live so far outside of the California culture of flower power and hippiedom, it could be another state altogether. Kathy Fagan, who hailed from New York City, studied at Fresno State after the illustrious Levine, Levis, and Soto were established as poetry icons. She asserts that by then, it was “like a Julliard for poets, this dusty little town with its shaggy trees and flat broiling avenues….it was a lively literary community in an unlikely setting.” She reports how Phil Levine demonstrated to his students the importance of concrete language, specificity, image, and detail: “He often said to us in class that we had more interesting things in our pockets than in our poems. And he was right. That lint, loose tobacco, and couple of cents were infinitely more interesting than anything in our poems, and more useful.”

Many of the poets featured here have interviewed each other over the years, and these interviews appear throughout. Juan Felipe Herrera interviews Luis Omar Salinas; David St. John interviews Peter Everwine; C.Z. Hanzlicek interviews Everwine and Levine; David Wojahn interviews Larry Levis, David St. John, Glover Davis; Chris Buckley interviews Levine, Hanzelicek, Salinas, Trejo, Soto, Veinberg, and Salazar. But that is only a sampling of the many in-depth interviews in this collection.

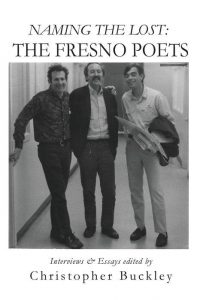

The book’s center reveals 31 black and white photos of Levine, Levis, Young, Buckley, Pape, Veinberg, Harper, and many more. The photos exude comradery and youth, beginning with the early 60s on up to the 1980s. They are endearing, casual glimpses into a time gone by preserved in the way of family photos—spontaneous and spirited. These are literary treasures that Buckley does well to include, contributing to the charm and charisma of Naming the Lost.

Unlike many compilations that tend to be dry and academic, this volume is lively, surprising, and rich in context and detail. Anything you may have wanted to know about the Fresno poets, their literary trajectories, relationships with fellow poets, and visions of what was possible in the art of the poem, can be found here. The word “tribute” is derived from Old French: tribut, and from the Latin tributum or tribus, meaning “tribe.” Naming the Lost: The Fresno Poets honors the “tribe” of thirty-four poets who expanded the palette of modern American poetry and, with thanks to poet Christopher Buckley, is now in our hands.

Maggie Paul is the author of Scrimshaw (Hummingbird Press 2020), Borrowed World, (Hummingbird Press 2011), and the chapbook, Stones from the Baskets of Others (Black Dirt Press 2000). Her poetry, reviews, and interviews have appeared in the Catamaran Literary Reader, Rattle, The Monterey Poetry Review, Porter Gulch Review, Red Wheelbarrow, and Phren-Z, SALT, and others. She is an education and writing consultant in Santa Cruz, California.