Tom C. Hunley: Review by Sonia Greenfield

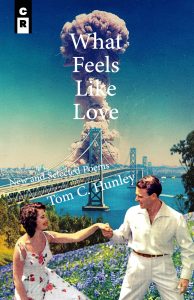

Tom C. Hunley: What Feels Like Love: New and Selected Poems (C&R Press)

What Feels Like Poetry: A Review of What Feels Like Love by Tom C. Hunley

If individual full-length collections offer a reader a unified experience, a deep dive into theme, say, or leitmotif, then a new and collected title is another animal and one that I am fond of, which is not to say that I prefer the one over the other; it’s a matter of what whim determines attention. However, what I particularly like about a new and collected is that I can see what a poet is up to now while also being able to trace things like the maturation of voice or the evolution of obsessions. Moreover, what is particularly true of a new and selected is that it’s essentially a greatest hits album, meaning that all the poems therein are selected carefully not just to represent the earlier book projects they have been extracted from, but also for their ability to stand on their own as experiences unto themselves. There are no B-tracks in a new and selected, as each poem collected should represent the best of what a poet can do.

Such is the case with Tom C. Hunley’s What Feels Like Love. The poems reach back to his second full-length collection, Still, There’s a Glimmer, from 2004, up to new poems presumably written in the past few years. What remains consistent across the collection is a sensibility that recognized the self as absurd in a world that is equally absurd. Thus, readers will often face a speaker comfortable enough with his existential angst such that he can hold it up for the reader to see, and then everyone, including the speaker of the poem, can laugh at it. A wry kind of humor can drive a Hunley poem about the hopelessness of it all, or tenderness can drive a Hunley poem about how brutal life can be sometimes.

Indeed, a Hunley poem will remind you, reader, that our existence is one of ambivalence shaded in tones of gray, or one where we wildly swing back and forth between joy and sorrow. It should be noted, too, that the accessibility of a Hunley poem, in terms of lyricism vs. narrative, does not sacrifice the complexity of human existence or the ways that language can skirt a topic too complicated for simplistic explication. Examples of this can be found time and time again, as when Hunley writes in “Slow Dance Music,”

I can’t explain the rain’s attraction to my head,

though I’m touched by its desire to touch me.

I also can’t explain unborn babies

sucking and blowing cigarettes bummed from

their young mothers, the absence of men from

the intricate inner worlds of their wives, or

the secret life of every dark street where

no one’s wrist has the time…

Hunley’s new poems in the collection are those of parenthood, which if you are a parent is a fraught experience and, in many ways, is the perfect way to define the concept of ambivalence, especially when dealing with children who are neurodivergent, as in the poems about his son. Joy, once understood as a simple concept, becomes complicated, and richer. Likewise, pain, when experienced in the context of the children we raise, becomes more saturating, as in the poem “Pounds,” when Hunley writes of his adopted daughter,

…her voice pained by a world

that had its foot on the scale ever since

she was born, freighted with the weight

of her birth mother’s drug addiction.

In fact, what becomes amply clear across many of the poems throughout this collection is that, insofar as Hunley is concerned, fatherhood is a weighty affair, which means it should be approached with both levity and gravitas, so you will find his poems on the topic playful but also underpinned with a kind of dead seriousness. This is because he understands, when it comes to the use of humor in poetry, that a spoonful of sugar makes the bitter medicine go down.

As a poet myself, I have always maintained that all poems are about creation, isolation, and disintegration, or some combination of these obsessions of human consciousness. If Hunley’s parenthood poems exist in the intersection between creation and isolation, with a peppering of disintegration, many of his other poems in the collection address the nexus between isolation and disintegration. Take, for example, the poems collected from Here Lies, his collection from 2018. Each poem plays out the death of Tom. C. Hunley, as in “Here Lies Tom C. Hunley, on His Hammock” or “Tom Ignored the Warning Labels,” though the poems—which address aging and love and, yes, death—have no answers; however, in imagining, over and over again, one’s demise, the poems have a Harold and Maude kind of sensibility, meaning, if one must meditate on death, at least have some fun with it.

The poems in the collection from The State That Springfield Is In provide the backstories for characters from the Simpsons, and as in many of the poems throughout What Feels Like Love, they are droll while also being touching. I understand the impetus to come up with stories to explain the often-baffling actions of others, which is what these poems feel like, in the bigger picture. For example, in “Officer Down,” we hear Chief Wiggum, Ralphie’s dad, expressing his confusion and love as Ralphie’s father. If you may recall, Ralphie was meant to be laughed at with his one-liners and simplemindedness. In the poem, we are made to feel guilty for having ever laughed at him, and we are even reminded about the pain that bullying causes—all that in a poem written in the voice of a minor Simpsons’ character. And, again, in terms of Hunley’s talent for humor, I laughed out loud when, in “Moe Szyslak,” Moe says, “Me, my last girlfriend left me, and she was a blowup doll. Stupid helium.”

Overall, this collection feels right for readers who might have big hearts, yet a taste for the maudlin; or readers who like narrative poetry, yet really love moments of surrealism; or readers who like poems that are whimsical in craft and language while being serious with subject matter; or readers who appreciate a speaker who is wise, perhaps even jaded by that wisdom, and who wants to be innocent again; or readers who both love their children and who are terrified of their children—in short, this collection of poems would be great for readers who want all of the complexity of life without the complexity of high lyricism, for example, or experimental syntax. Indeed, the poems do not suffer from a lack of either.

Sonia Greenfield is the author of two full-length collections of poetry, Letdown (White Pine Press, 2020) and Boy with a Halo at the Farmer’s Market, (Codhill Poetry Prize, 2015). Her chapbook, American Parable, won the 2017 Autumn House Press chapbook prize. Her poetry and prose have appeared in the 2018 and 2010 Best American Poetry, PANK, Washington Post, Willow Springs, diode, and elsewhere. She lives with her family in Minneapolis where she teaches at Normandale College, edits the Rise Up Review.