Thomas Aslin: Review by Jeff Knorr

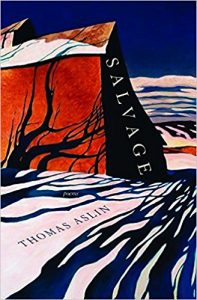

Thomas Aslin, Salvage (Lost Horse Press)

Touched by The Wind

One of the great gifts of naturalists, historians, and anthropologists is to offer us the details and narrative of a land, a time, and a people’s actions. But often, what gets missed in the observations is the importance of our human experience and endeavor, essentially what it means to be alive in some place during some time. Hence, we find the importance of the poet, the observer of the world who, as James Dickey said, “has to be more human than other humans.” In Thomas Aslin’s newest collection, Salvage, he does just this. Aslin captures the people of his family and others as the representative people of eastern Washington in the mid-twentieth century. What’s more is that he captures the intricate details of the land and uses this as the metaphoric internal landscape of a hard life in a hard land that provided beauty, bounty, and crushing defeat.

Thomas Aslin opens Salvage by going back in time to childhood and invoking his uncle as an iconic figure of his family as well as the town. He opens the first poem, “Finding My Uncle at Donna’s Café” with the stanza:

I find him there chewing on a toothpick

and chatting with friends before rising

from the table, before tossing a quarter

in a bowl for a cigarette. Back at the house

he touches the scar over his left brow,

says an English doctor saved his life,

then rolls up his pant leg to reveal

a scar like a small, white squid.

He says it was a dum-dum bullet broke his tibia.

“Can you believe it?

I was shot by a twelve year old.

The poem continues and paints the landscape of eastern Washington as well as the landscape of this home. It is clear in this casting back that the narrative of family was a kind of balm against fears of the future, many of which become realized in later poems. And finishing the poem Aslin writes:

…when I was small, I’d pry my bedroom door

ajar so I could hear my parents, my uncle and aunt.

Even from my room I knew my uncle

draped his forearms over the back of that kitchen chair,

that he rode the chair as if astride

a piebald pony, cutting a sickly heifer from the herd.

Laughing, the men smoked, sipped their beer.

The women spoke of white sales and children.

This is not only the beginning of many poems that capture the family but the constant watching of a small boy who continues to watch with fear, love, admiration, and scorn.

In this early portion of the collection Aslin courses in and out of poems of the older persona, the one who views his own adult life as the product of the poets and friends he has picked up along the way and the shaping by his own people. In the poem “A Bus Driver’s Journal” he contrasts the harsh interior landscape of an urban life against the more spacious landscape of the rural life. And we come to meet poetic icons of the Pacific Northwest who not only shaped Aslin but the larger linguistic landscape of the west. We meet Ray Carver, Madeline DeFrees, and Richard Hugo. We encounter the young Gary Thompson and Tom Crawford and Paul Zarzyski. All of these figures show up woven into the tapestry of the place—the small bungalow of DeFrees, Trixi’s “Antler” Bar with young poets drinking and singing.

About a third of the way through the collection Aslin makes his first movement between sections, the way a piece of music moves from the first movement to the second. In the poem “Palouse” he turns us directly back to his life in valley, the difficulty and the bounty of living a rural Washington farming life. He opens “Palouse” with the lines:

From a distance, a patchwork of fields.

On the butte a blue-eyed grass, a gully wash,

variegated light in the fescue. Wildflowers…

By the middle of the poem, Aslin has moved to noting more than the land but the nuanced existence that comes with such a place.

…Years ago flour

mills built along the Spokane River fed

a local need for bread. If not for this, for the cattle,

the hay bales and sacked grain, these fields

would seem merely ornamental, even in the clear wash

of a pocked moon or wheel of sun rising.

It is this poem which announces for us the movement of the heart through the land, the reminiscence of the work and families that inhabit it. This section continues with retrospective poems of the young lives of not only the son in the family but even the young lives of a mother and father separated by war, separated by the difficulty of a rural life, and even separated later through discord and finally death. While there is a tenderness in this section to some of these memories (yet never sentimental, Aslin knows how to toe that line and not cross) there is a deeper sense of harm and tragedy. It comes again and again in poems such as “Looking Through Photographs at Her Sister’s House,” “Drifting Toward Sleepin Hedgerow, Normandy, 1944,” “Horse Piss,” and finally the haunting last lines of “Winter Solstice” as Thomas Aslin writes:

…At dawn the man

herds his steers into a corral and shoots every

damn one. Pours diesel over each animal,

then touches off a guttering fire. Even as

an underbelly of cloud settles in beneath the sun,

it’s the three year old finds his father hanging in the barn.

Aslin never loses his grip on the image and does the emotional work in the poems through the image. His mastery of the subtle metaphor crafted out of the land allows us to come to terms with the difficult people who are our families and the love that envelops us in these constellations of family members.

In the final movement of Salvage, Thomas Aslin takes a turn into the deep feelings of loss as mother and father die, as the relationship with a brother becomes distant and bitter, attaching itself to the old chronic angers of the house. And yet, it is in this section where Aslin is at his best as a contemporary American poet of the West exploring his own philosophical and spiritual questions, asking how to find the sacred in the profane. Aslin at the same time evokes a tenderness toward the mother in such poems as “A Mother’s Hand” and “Because My Mother Was Beautiful.” Aslin writes in this poem, “She was as they said then, / comely. Even in her thirties, she turned heads.” And at the end of the poem as the persona stands next to the mother’s casket he writes:

And by standing near her,

as if in still water,

I gazed at her without shame

for as long as I wished.

These lines finish a poem that not only emotes the loss of the mother but touches on the deep longing for the return of the dead. These feelings continue in following poems and also then move to the loss of the father, the loss of the family. And it is in the face of this monolithic loss of the ones we love that the spiritual ruminations rise. Aslin asks deep questions of our being in “Heart of The Coleus” when in section 2 he writes:

What is left to forgive

when all one remembers of her

besides a prolonged absence

is her inimitable smell and voice?

And he continues in this poem ruminating on the loss of the family members, the uncle in the opening poem, the mother, the father, the poet who drinks himself to death. And in a searching for more, the attempt to find something like small gods in the land Aslin writes:

I am not ashamed to say I speak to the dead.

Though even when the wind touches my shoulder,

I seldom hear voices. Only in dreams am I sure

to hear their voices.

The loveliest dream is a river that follows

its own sorely made path and seldom wavers.

This path, the metaphor of all our own sorely made paths, can lead us to some salvation, some kind of rising from the depths of longing and despair of the great human loss we are all part of. The poet continues through the end of the book reminding us that as we age, as we move through our own arc of time and watch it shorten, we ought to soften the edges, let the old grudges fall away. If we don’t, the tragedy of isolation may grab ahold of us and sweep us into some lone space as empty as the valleys of eastern Washington. Aslin writes at the end of the collection in “Before There Was Light”:

With so little time left

why not speak in calmer tones?

There was a time when I was fearful

of the dark and could not sleep.

I was not much more than a baby.

An older brother, who no longer

speaks to me except in anger,

held my hand. When he told me this

not so long ago I remembered

the anger that flared like ground fire

in that house while Father was alive,

then flared again when he died.

This is the warning, the sounding of the bell for us to lay aside what is divisive in the short time we’re here. And finally, Aslin finishes the collection with the title poem “Salvage,” which is a poem that reminds us about connection and support. That the love we offer each other that leads us to our own personal quest can lead us to find some salvation, in fact maybe even “my own blue-eyed Jesus.”

Thomas Aslin has written an outstanding collection of poems in Salvage and certainly laid claim to being one of the powerful voices of western American poetry in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. He has spoken in these poems from the family of other great Northwest poets and offered a view of the land central to our being, to our own journey on this planet. His power lies in the understated but authentic voice and his ability to capture us continually in metaphoric images which launch the poems to the lift of the lyric. And lest we think this is just a book of free-verse poems about the west, Aslin shows remarkable dexterity punctuating the collection with fixed form poems from the sonnet to the ghazal to villanelle. Let us praise these poems the way these poems come to praise our lives and let us find the marvelous in front of us the way these poems lead us into the marvel of living.

Jeff Knorr is the author of the four books of poetry, The Color of a New Country (Mammoth Books 2017), The Third Body (Cherry Grove Collections), Keeper (Mammoth Books), and Standing Up to the Day (Pecan Grove Press). His other works include Mooring Against the Tide: Writing Poetry and Fiction (Prentice Hall); the anthology, A Writer’s Country (Prentice Hall); and The River Sings: An Introduction to Poetry (Prentice Hall). His poetry and essays have appeared widely in literary journals and anthologies. Jeff Knorr is Professor of literature and creative writing at Sacramento City College.