Lauren Camp: Review by Ann Fisher-Wirth

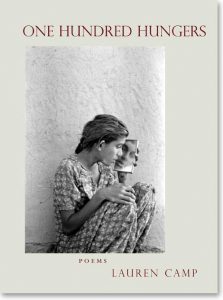

Lauren Camp, One Hundred Hungers: Poems (Tupelo Press)

“We think back through our mothers if we are women,” Virginia Woolf claimed in A Room of One’s Own. Lauren Camp’s third book of poems, One Hundred Hungers, shows how profoundly and with what longing we also sometimes think back through our fathers. One Hundred Hungers, which won Tupelo Press’s Dorset Prize, focuses on her Jewish father’s boyhood in Iraq during a time of harmony between different religious and ethnic groups—Iraq, with its “stalls of lemons, honey and wool” and the “lithe lines of sun in a city grown to the cadence of water” (“Pauses” 41). In June 1941, as the book’s notes tell, a two-day massacre of Jews in Baghdad, the Farhud, inaugurated a darkening political atmosphere that intensified during the 1940s. Eventually, in 1950, the father’s immediate family immigrated to America.

They grasped their new worth in a suitcase

and boarded a plane.

They traveled through clouds

and arrived in a place with no fruit market or river no goats at the

door.

They swore they had forgotten would forget. (42)

Then began a lifelong dispossession—the past held to the heart through ritual and, as these poems so richly recount, through the foodways of the lost world, prepared by elders (mostly grandmothers) who attempted to appease but can never appease the one hundred hungers. An astonishing poem, “One Hunger Could Eat Every Other,” describes the rituals of what Toni Morrison has called “rememorying”—in this case, re-creating a broken past, at family gatherings, through eating

for years and years. We eat like beggars. We eat to the bones and the edges of our plates. We eat the road they took to get here, the many myths they left behind. We grab with our hands, our mouths still full. We eat until the tablecloth is stained with conversation and the severed tongue of a cow, beet-grief, the village air. (8)

“The thick line of life is all hunger,” writes Camp (9). This book explores various iterations of hunger, or desire; it includes a strong group of poems about adolescent sexuality, sexual harassment, sexual desperation, and finally a lasting love, celebrated in the beautiful poem “Married”:

What did I know of the future or past?

Whatever we speak resembles flowers. Do you believe in God? No—

Or Yes, I’ve studied it.

More than 600 million seconds: our permanent abode. . . . (78)

But above all, in this book, the hunger is the daughter’s, to know the father—a father who cannot really be known because he has shut the door of his past behind him and does not want to talk about it. As one poem declares, “If he missed his country, / her father never said” (“If He Missed His Country” 44). And another: “My father hears nothing and nothing becomes the gate / he walks through. There is nothing / but what has been erased” (“Pause Hawk Cloud Enter” 5). The shut door extends to the present; “Why Dad Doesn’t Pay Attention to Iraq Anymore” describes a man who, “when Hussein’s statue fell,” stayed

up in his condo,

organizing pencils, most with erasers,

his radio turned to Beethoven’s Sixth

or some college football. Collateral damage,

snipers, missiles, vessels and hostile

attention: he’s not watching…

because, heartbreakingly,

All he wanted was some portion of yes

and stay, those phrases no one could pack. (54)

At several points, barred from direct access to information, Camp writes “variations”—poems as if the father had decided to speak. “Let’s pretend you tell me what happened,” “Variation: Let’s Pretend” begins:

Because I need it, you tell it:

the habits, the scarring, the shuffle of leaving

your home. You won’t make me keep waiting. (27-28)

But the poetry of this book is not born out of such forthcoming. Instead, the book hovers around loss—the father’s loss, the loss of a once-harmonious culture now war-torn and in ruins, and therefore the daughter’s loss of a knowable parent.

“Memory is the sense of loss, and loss pulls us after it,” Marilynne Robinson writes in her novel Housekeeping. Still, memory is also an act of retrieval, as in the lovely poem “Foreign,” which describes a day when, three years old, the daughter went with her father to his office on Wall Street and kept him company, typing one-fingered, going on the elevator, eating lunch with him at Chock Full o’ Nuts where, “[t]hough everyone talked, she heard nothing but Dad” (14). The tastes of foods that he ate in Iraq are another way of knowing him, as Camp writes in “Butter and Prayer”:

The girl’s father is the divinity of a pomegranate, a pith capping the slow mantra of seeds and the rich sweat of juice. He is a fried egg on a plate, simple and circular, a feast of pistachio and apricot, a pot of rosewater tea. . . . He is a platter of tripe. His love can be tasted. She doubts nothing eats everything with a rigor of claiming her parent. But where the sacred spread of food ends, so does the taste of her father. (30)

Memory, then, must be wedded to imagination, based on the smallest clues of what can be known, as in “Letter to Baghdad.” I wish I could quote all of this poem; it is an unforgettable poem in a remarkable book. Here is the second half of it:

One day we were talking about beginnings, and I had begun.

I wasn’t at the center anymore, and we kept letting in a little air,

and he showed me a word for the boy he once was

and he showed me this Arabic word and in this way I knew

this was the most authentic mourning I would ever see.

And I saw it and he said it again,

and we were covered with it. Entirely covered. This was his home,

he said, as he gave me the address, the place

where the first time and the spurned and the color

and the milkmaid stood in the alley. And even though he didn’t tell me

about yesterday and the day and the day and I never saw

any other way to tell it I never saw

heaven or the land that was black, one day I knew enough

to take the word from him and sip

every little thing every steeped thing

and there were many trees and not enough cold and we sat

by the river that curves in every direction and our hearts

lifted up to the birds. (62-63)

I cannot praise this poem enough. Just go buy One Hundred Hungers.

Ann Fisher-Wirth teaches poetry and environmental literature at the University of Mississippi. The author of various books of poetry, she has also published work in numerous literary journals, including Florida Review, Georgia Review, and Kenyon Review.