Diane Lockward: Review by Pat Valdata

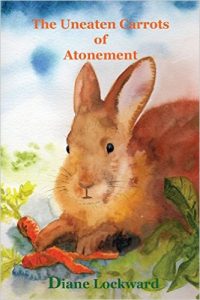

Diane Lockward, The Uneaten Carrots of Atonement (Wind Publications)

Diane Lockward’s fourth full-length collection is a masterful mix of humor and horror in poems about life, its losses, and cruelties both minor and major. The rabbit on the cover looks both mildly surprised and a bit guilty about the uprooted carrots under his paws, as if he is aware that bad things happen to rabbits in some of the poems in this book.

Bad things happen to people, too, as “The Phone Call” makes clear, leaving a couple “like two shadows, the sorrow / between you a cord stretched” (page 12).That sorrow crops up in other poems in this collection, but as the same poem reminds us, it is also about “the business of breathing in / and breathing out” (page 13). Lockward does a masterful job of balancing dark subjects like sin and guilt, divorce and death, with surprising touches of wry and empathetic humor. In a poem with the amusing title “Pity the Poor Fortune Cookie Writer His Muse,” Lockward presents not the writer himself, but the person who reads his output: a widower who whose “tears run like the Yangtze” when he reads “Even a small gift brings joy / to the whole family” (page 91).

Lockward is an attentive observer of both human nature and the natural world, whether she is writing about promiscuous squirrels under a birdfeeder who “performed lewd / sexual acts as if / to satisfy one hunger / might satisfy another” (pages 81-82), a mushroom that looks like a ‘[s]quat tree, rubber umbrella, a one-legged stool” (page 40), or a cashew “curled like a baby’s ear moon” (page 31). Her flair for the crisp and funny phrase is evident in several list poems that catalog colors, the contents of an ossuary, forms of light, and, in “How I Dumped You,” at least 16 ways to leave an ex:

…I dumped you like an old tire onto the highway.

I violated a local ordinance and hurled you like a bagful

of dog-doo onto someone else’s yard, tossed you like

watermelon rind after a picnic, like a brown banana peel,

like a used Kleenex, like a dead chipmunk. I scraped you

from the sole of my sneaker like a wad of chewed-up gum. (page 18)

Lockward is also skilled at incorporating formal elements into her work. Her sestina “Why I Read True Crime Books” has varied line lengths that lend subtlety to the end-word repetitions. Half-rhymes mask the terza rima of “In My Yard, the Bones of Trees.” Offset lines suggest birds’ wings in “Where Feathers Go When They Fall.” Other poems use regular stanza forms, some with clever rhymes (sugar / hug her / blubber), but many lack rhyme altogether, instead using the semi-formal stanza structure to propel the arc of the poem. In “For the Love of Avocados,” Lockward enjambs the last line of each four-line stanza until the next to last. The poem uses the image of the split avocado as a metaphor for children who leave home “hardly more than a child” and return home (presumably from college) as grown adults, the “broken pieces, made whole again, merged / into two reconstructed hearts, a delicate and rare / surgery.” The poem ends with mother and child sharing the avocado, “forks slipping into the buttery texture / of unfamiliar joy” (page 51).

The Uneaten Carrots of Atonement is full of small moments like that. Sometimes, loss is transformed into connection, but mostly it is not. Snap decisions, sudden falls, or even the slow unraveling of long relationships all have painful consequences that we cannot foresee or take back. Lockward’s book explores, with great beauty, those intimate cause and effect moments. Her speakers are unafraid to see the world as it is and to make peace with the worst and best it offers us all.

Pat Valdata is a poet and novelist. Her new book of persona poems about women aviation pioneers, Where No Man Can Touch, won the 2015 Donald Justice Poetry Prize. She lives in Elkton, Maryland, and is an adjunct professor at the University of Maryland University College (UMUC).