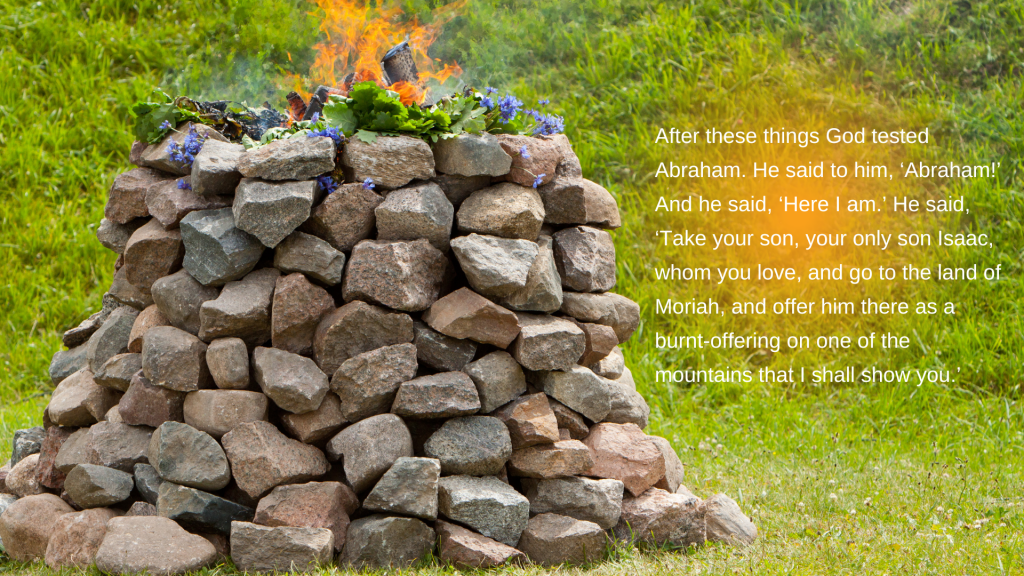

Being called to sacrifice

…God tested Abraham, saying to him… “Take your son, your only one, the one you love, Isaac, and go forth to the land of Moriah. Offer him there as a burnt offering, on one of the mountains I will show you.”

[…]They came to the place that God had shown him. There Abraham built the altar and arranged the wood and bound Isaac his son and laid him on the altar, upon the wood. Abraham now reached out and took the knife to slay his son, but out of heaven an angel of the Eternal called to him, saying: “Abraham, Abraham!…Do not lay your hand on the lad; do nothing to him; for now I know that you are one who fears God, as you did not withhold your son, your only one, from Me.”

Genesis 22:1-2, 9-12, trans. Chaim Stern

A friend of mine brought this story – traditionally called “The Binding of Isaac” – to his philosophy classes when he was teaching Kierkegaard. He said he always noted a stark difference between the way Christian students and non-Christian students reacted to hearing the story.

Christians, having known this story since they were young, found it familiar. They had probably already been taught how to make sense of Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice his favorite, long-promised, miracle son. After all, St. Paul made Abraham’s great faith in God the cornerstone of his argument about how we, too, are “justified by faith in Christ, and not by doing the works of the law” (Gal. 2:16). And the Church encourages some poetic correlations between Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice his own son and God’s willingness to sacrifice Jesus – especially as we read this story near Good Friday and Easter. So, the Christian students had made peace with the Binding of Isaac – had perhaps always been at peace with it.

Non-Christian (and presumably non-Jewish and non-Muslim) students heard the story for the first time and were shocked by it. They wondered aloud about how God could ask for child sacrifice, about how Abraham could possibly assent to such a horrible thing. Their reaction encouraged Christian students to read the familiar story with new eyes, understanding the full dramatic (and theological/ethical) impact of the Binding.

As a Lutheran Christian, I’m of course a big fan of Paul’s justification argument in Galatians, whose foundations are in Abraham’s saga. And also, as a Christian with a particular interest in violence in scripture, I have set up my tent among the people who continue to find the Binding a deeply disturbing story – and honestly, I want to keep it that way. And also, I’m a university pastor about to preach on this story to a group of students who will definitely not be coming out in the 10 p.m. cold and dark just to hear me say, “This is hard.” They’re not coming to hear about my struggles – they’re coming to encounter God.

As I’ve prepared to first hear and then share a Gospel message from this disturbing story, I’ve found my spirit drawn less to interpretations that emphasize Abraham and his faithfulness – and more to interpretations that emphasize the God who inspired such faith in Abraham.

So let me tell this story in a different way, beginning with a question: Why would Abraham – who boldly argued with God over the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah in Genesis 18 – not raise a single objection to God’s order in Genesis 22 to sacrifice the son he had been waiting for years and years? Did his Kierkegaardian trust in God only develop in the years those chapters represent?

An answer may lie in this: that in the time and place of Abraham, child sacrifice was a commonly-accepted part of religion. So Abraham hears the voice of elohim (a Hebrew word that was a generic term for “God” or “gods”) telling him to sacrifice his child, and it seems like a reasonable (if devastating) request for a god to make. Maybe he had been formed by his culture to think, “That’s just life.”

Yet when Abraham raises the knife, an “angel of the Eternal” stops him. And here the word used for God (“the Eternal ”) is not elohim, but YHWH – the same word by which God is named to Moses (Ex. 3) – a name not for any god, but for the God of Israel. Perhaps God is not only testing Abraham, but teaching him: Other elohim may desire child sacrifice; but I, YHWH, do not. And indeed, in the law given to Moses, God repeatedly forbids child sacrifice (Lev. 18:21, 20:2; Deut. 18:10). Abraham is willing to sacrifice as much to his God as his neighbors are to theirs, but the God of Abraham does not require such things from us.1

Even so – why did God test Abraham in this terrible way? All that we hear from God in scripture is: “Now I know that you are one who fears God, as you did not withhold your son, your only one, from Me.” All that we can be certain of is that God wanted to see that Abraham would listen and obey – even when it came to the person that he held dearest – even when it looked like it would endanger all that God had been promising to him for years.

So maybe that is the clearest lesson left for us: that God “may require of people in every age to give up that which they love most, and often asks not the expected but the awesomely unexpected.” 2 And this characteristic of God does show up in our lives in so many ways: going to worship, expecting to be comforted, but finding ourselves made uncomfortable; seeking the true God amidst the familiar false gods of our own culture; being called to real, difficult sacrifice of time or money or desires. Perhaps the great power of The Binding for Christians today is to turn us, with serious hearts, to the words of Jesus:

“If any want to become my followers, let them deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me. For those who want to save their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake, and for the sake of the gospel, will save it.” -Mark 8:34-35

Pr. Kate

March 22, 2023

Rev. Katherine Museus Dabay serves as university pastor at the Chapel of the Resurrection at Valparaiso University and takes turns writing weekly devotions with University Pastor James A. Wetzstein.

1 From essays on The Binding of Isaac (the Akedah) in The Torah: A Modern Commentary, rev. ed., W. Gunther Plaut, general ed., (New York: URJ Press, 2006), pp. 141.

2 Plaut (ed.), pp. 142.