It’s a Matter of Trust

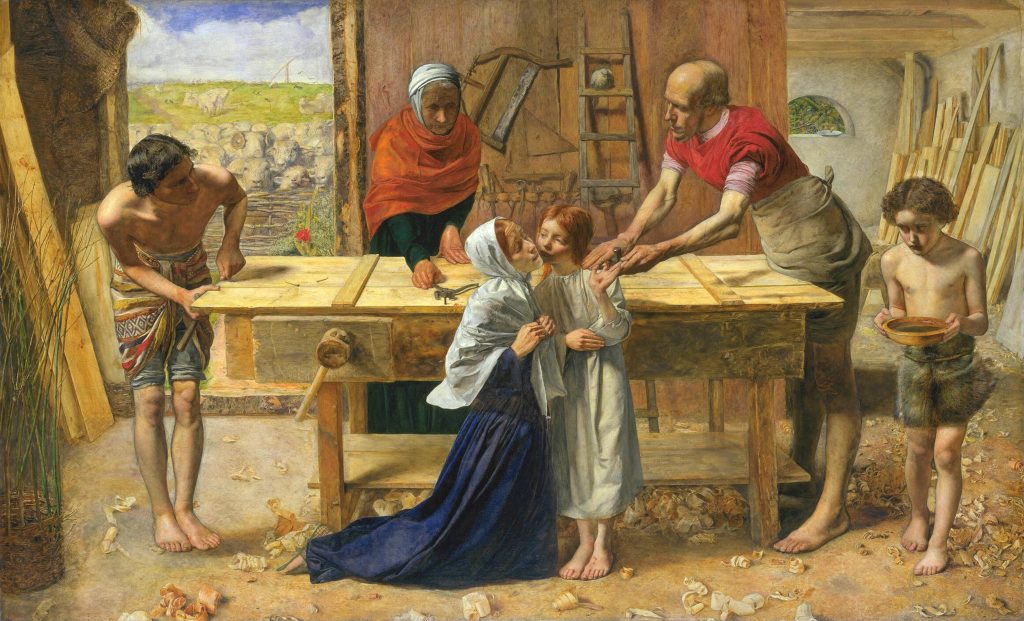

This painting caused an outcry when it was first exhibited following its completion in 1850. None other than author Charles Dickens decried it as a scandal for its gritty portrayal of the Holy Family. Describing the portrayal of Jesus, he wrote, “In the foreground of that very carpenter shop is a hideous rye-necked, blubbering, redheaded boy in a bed gown, who appears to have received a poke in the hand from the stick of another boy with whom he has been playing in an adjacent gutter.”1 The painting was the work of John Everett Millais, a member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, a group of artists, poets, and critics who saw their work as an effort to reform the arts toward a more careful attention to reality as it really was and not as “sloshy” academic artists rendered them in their convention-bound portrayals. The scandal of this painting was so intense that it caused some to leave the association of the Brotherhood because they feared that this work and that of others threatened to disgrace Christianity.

These sorts of concerns are likely now regarded as quaint. What Dickens saw as scandalous, (especially ironic in light of his portrayal of London poverty in his writing) we might view as refreshing for its more honest, unfiltered, portrayal of life in Joseph the carpenter’s workshop.2 This is not the idealized portrayal so typical of the Renaissance. There are wood shavings and dirt everywhere. The characters even have dirt under their toenails!

But the question over whether or not the characters in the painting look sick and destitute or honestly portrayed as rugged and hardworking risks missing the mark of what makes this painting so compelling. The scene is rife with symbolism that serves as dramatic foreshadowing for the saving work of the Christ-child who stands in the center, compelling his mother’s devoted attention.

Joseph, standing just off to the right, is bearded and nearly bald – thought by tradition to have been much older than Mary. He is working on a door. We see it laid across his carpenter’s workbench. Nails in the door lie exposed and it appears that the boy Jesus has cut his left hand on one of the nails. He holds it up for Mary to inspect the wound and in doing so, allows drops of blood to fall from his hand and land on his foot. Mary offers her cheek for his kiss. Millais is inviting us to recall the wounds of Christ on the cross and Christ’s devotion to his mother, even in that hour. An older woman stands behind the bench, reaching for pliers, a tool associated with bringing Jesus’ body down from the cross. She is likely Anne (or Anna), the name given to Mary’s mother by tradition. Her name is a form of “Hannah” who was the unlikely mother in the book of 1 Samuel whose song Mary reworks as her Magnificat. Off to the right, a boy wearing only animal skins brings a bowl of water to wash the wound. This is Jesus’ cousin, John the Baptist, who will baptize Jesus in the water of the Jordan. Behind John, barely visible, a single bird drinks from a dish of water set on the window sill. Another bird, clearly a dove – the Holy Spirit – sits on a rung of a ladder, like the ladder used to retrieve Jesus’ body from the cross or is it Jacob’s ladder? Next to the dove, a carpenter’s triangle recalls the doctrine of the Holy Trinity.

While all of this action takes place in such a symbol-rich environment, a young man on the far left bends to get a better view of all that is happening. He represents all of Jesus’ future apostles who will be witnesses to Christ’s death and resurrection. Finally, behind it all, a herd of sheep gazes intently through the doorway. They are the only ones whose eyes meet ours as though they know that we know what will happen.

This painting works because we know how this story goes and the thought of this scene playing out among characters who don’t know what’s going to happen next adds to the intensity of the image the way a predictable horror movie draws us in with anticipation.

The real Joseph, on the other hand, had no idea what was going to happen next. Matthew relays the account of his initial confusion and then well-intended planning. He is dissuaded from this path in a dream. Matthew writes as if the path forward for Joseph is crystal clear, “When Joseph awoke from sleep, he did as the angel of the Lord commanded him…”3 If we’re honest we’ll have to admit, a dream doesn’t seem like much to go on.

It’s not much to go on, because most of us don’t put much stock in our dreams. Mine tend to be pretty crazy, especially when I’ve taken NyQuil before bed. They are not trustworthy conveyors of reality.

Trust is at the center of it. Joseph acts because he trusts what he’s being told is true.

What do you trust?

Joseph’s dream angel anticipates this question. The angel essentially says, “Hey, don’t take my word for it! Remember the prophet [Isaiah’s] words: “Look, the virgin shall become pregnant and give birth to a son, and they shall name him Emmanuel.” 4

We have that same word, only the word in our possession has the benefit of the whole story, laid out in a big tableau like Millais’ painting. We know how the story goes. We have the testimony of the Apostles who watched it all happen. We have the witness of the Early Church who worked to sort it all out, seeking to understand and describe the Christ event as best they could because, as a phenomenon, it was undeniable. We have the example of generations of trusting and trustworthy believers who acted out lives of love and service because they trusted in who God claimed to be in Jesus Christ.

Now, at this stage in our stories, our trust is the same. The Holy Spirit, like a dove perched on the rung of a ladder, is present for us regardless of the scene in which we find ourselves.

Peace and joy,

Pastor Jim

Dec. 7, 2022

Pastor Jim and Pastor Kate take turns writing weekly devotions for the Chapel of the Resurrection.

1 Dickens is quoted in this short video.

2 If he was a carpenter at all. The Gospel according to Matthew identifies Joseph by his trade as a tekton – a builder – and there’s some debate within the early Christian tradition over whether he worked in wood or stone.

3Matthew 1:24

4Isaiah 7:14