Mercy makes us uncomfortable

For all of the familiarity of the Jonah and the great fish story it has been subject to a wide range of interpretations. Some regard Jonah as an ultimately faithful, albeit reluctant prophet, while others see him as an infamous example of disobedience and dissent. Some have read this account as a historic event, while others see it as a broad parody illustrating how humanity is engaged by God.

Regardless, what comes through in every retelling and analysis is the recklessness of divine mercy and forgiveness. At every turn, human fickleness and failure are met with divine forbearance and maneuvers that somehow, perhaps implausibly, work to bring human actors back to their senses, as the undeserving recipients of divine grace, mercy, forgiveness, and life.

Maybe that’s why Justus Jonas, the 16th-century theologian, and colleague of Martin Luther, took Jonah’s name for himself. His first name was Jobst, not an uncommon name in German culture. Still, like many of his academic colleagues, who are enamored of the new learning of the renaissance, he changed his name as a mark of intellectual self-expression. “Justified Jonah“ or “Righteous Jonah“ – it’s a curious choice given the fact that his dear friend Luther regarded the biblical Jonah as an example of all that was wrong with people.

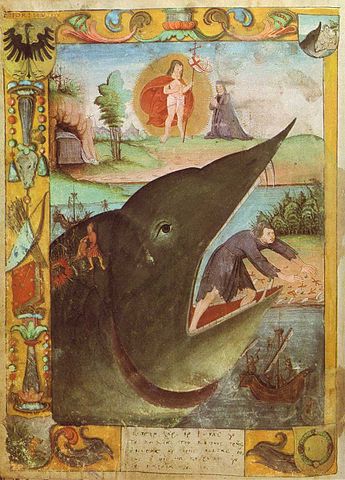

Justus Jonas even goes so far as to take an illustration of Jonah’s story as a kind of personal logo. As seen here, the central feature is the moment that the fish expels Jonah onto dry ground. It’s a resurrection of sorts. All around this large image are smaller presentations of moments in the rest of the story. Jonah embarking on his journey of defiance appears on the great fish’s back. Down in the lower right, Jonah is being thrown overboard and just to the left of the fish’s eye the sailors are offering their sacrifice of thanksgiving to God. One scene stands out both visually and thematically at the center top. There, we see the figure of Jonah. He’s recognizable by his brown robe, which looks like it might be Justus’ professoral robe. Jonah is being confronted by someone remarkable for his lack of clothing. Loosely, wrapped in white linen, the figure holds a cruciform staff from which flies a banner. The traditional symbolism is distinctive. This is the way the newly risen Christ is frequently portrayed. Jonah is meeting (or being confronted by) the resurrected Christ in an anachronistic way. Why would this be happening? Is Jesus calling Jonah out? Is he offering him a resurrected life after the tomb of the fish? Is he showing Jonah his own out-of-the-fish/tomb experience? Is he forgiving him? Is it all of the above?

The image is as narratively ambiguous as is the story of Jonah itself – as ambiguous as our own stories of guilt and forgiveness. As much as we may cherish the knowledge of our forgiveness by God, being forgiven by another person or receiving mercy from them is discomforting. Typically, we hate owing others. We would rather lay claim to our own rightness ourselves. And don’t get us started when people who are notoriously sinful receive some measure of blessing or mercy. Usually this makes us as upset as Jonah was at the end of the story.

Yet the mercy of God is relentless. Jonah will not go unpursued. Ninevah will be shown mercy. You and I will be confronted by the risen Christ every time we gather with others in his name.

This Sunday is Palm Sunday. Jesus will be riding into Jerusalem like a conquering king of love.

He’s looking for you.

Pr Jim

March 29, 2023

Rev. James A. Wetzstein takes turns writing weekly devotions with Rev. Katherine Museus Dabay at Valparaiso University, where both serve as university pastors.