Meghan Sterling: Review by Daria Uporsky

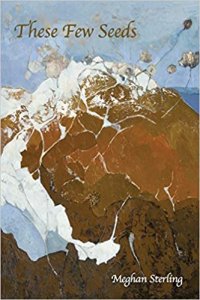

Meghan Sterling: These Few Seeds (Terrapin Books)

“The Truth, No Matter How Much it Hurts” in Meghan Sterling’s These Few Seeds

Can a sounding alarm be exquisite? If so, it would ring in the ears with the same rich timbre as Meghan Sterling’s These Few Seeds (Terrapin Books, 2021). Her debut full-length poetry collection poignantly captures the urgency and pervasiveness of climate change through the lens of love. Although the poems discuss personal and world events, as well as the past, present, and future, readers feel rooted to a single place throughout the book. Sterling holds us in this safe place, ensuring her readers do not feel scattered, while she shape-shifts to accommodate our twenty-first century circumstances in a multitude of contrasting parts, times, and selves.

Early on, Sterling tells us she boldly made a pact to love everything unconditionally, and it is from this place of love that she lays bare truths we cannot ignore. We continue to read the poems feeling validated or comforted by Sterling, but also gently elbowed into rumination. We close the book both pondering and fully knowing just how we got to this moment, and what it indicates for future generations. This—a perfectly estimated gift from a profound poet to a world set askew.

Setting the tone and sense of place, the book begins with “Morning Prayer.” We revel in Sterling’s exuberant love for her husband and daughter, but she is quick to juxtapose this with the uncertainty of pending environmental concern looming over them, and all of humanity, “It is the beginning when there was you and me and her / and the water that’s rising— / oceans, lakes, rivers, streams….”

As residents of Maine, Sterling and her family clearly have an interconnected relationship with water, and rising water is a recurring image in the collection. By positioning various climate imagery within the context of her child’s innocence or their parental love, Sterling offers a fuller scope of her experience both as mother-wife and as poet witness to our environmental circumstance.

Sterling continues to nestle her readers into the cozy home life she has with her daughter and husband. She writes in “Adeline,” “In our house, we always have dusty window frames, / glass jars of tea, loose scree on the walkway.” We narrow into a stronger sense of place with more intimate scenes, as in “Man Subdues Terrorist with Narwhal Tusk on London Bridge” where Sterling’s husband knocks on the door while she is in the bathtub. He asks her if she has heard the news about the terrorist and the narwhal tusk, and then walks away, chuckling to himself.

Sterling also outlines her moral code in the first section, resting on a framework of unconditional love. In the travel poem “Memory is a Greek Island,” she writes about climbing a hill overlooking a harbor. In this moment, she makes a moral decision, “I decided here to love all that I was given, / no matter how much it hurt.” Later, Sterling will rely on our understanding of this when she digs deeper into environmental warnings and global crises.

Parts Two, Three, and Four of These Few Seeds build atop the groundwork Sterling lays in the first section. We come to better understand her relationship with her daughter and husband, her heritage, and her thoughts on the past and future. Her love for her daughter often juxtaposes personal failure or feelings of desperation. In “Daughter,” Sterling writes,

The waves of your soft hair

are all that stills the thrashing of a heart

that’s been submerged and drowned

a million times over.

I need you to be safe….

Our emotions tumble from appreciating her child’s loveliness to deeply wanting her to have access to a safe world. In “All That I Have Is Yours,” Sterling questions whether devastation can birth new life. The answer comes at the end of the poem. She writes, “And I broke apart / and turned you into being, choosing / to go as I had gone before, but braver.” We cogitate over whether or not this is advice cloaked in a personal story of childbirth. Perhaps we also need to be braver in order to birth something new from our global disasters.

But Sterling adequately intersperses poems to convey her deep appreciation for life and the overflowing love she has for her family. In “Center Line Rumble Strip,” she describes her husband’s absence like “heat” and “steam sputtering” off of her skin. She recalls their early years, when they “could slip easily / into connection, sleeping like doves in the eaves….” She remembers this fondly, but makes it clear that it was her daughter who “woke” and “revived” a deeper sense of love in Sterling and her husband. In “Bliss,” she writes that her heart grew, “big and bright / like the heart in the middle of the page when I write / Mama loves you.”

Although it is referenced only once, reading about Sterling’s relationship with her mother offers depth to the entire collection, painting the poet more vividly in our minds. It is in stark contrast to her relationship with her daughter. In “Queens,” she begs to be the opposite of her mother, “Remind me that I will be different … because I am not / stopped, plugged, choked, blocked, or bolted.”

In continuing to build the familial lens, and again offering context and depth, Sterling reveals her Jewish heritage. Her current connection to the religion entails her upholding small but meaningful traditions and contemplating its spiritual depths. In “Jew(ish),” Sterling introduces us to the knick-knacks of Jewish life. “In our home, small traces, only: the menorah / in the cupboard, a mezuzah in a drawer….” But it is “Mincha, Afternoon Prayer, Meaning ‘Present’” where she more deeply discusses spirituality. She describes a scene in a synagogue in which wives elbow their husbands “to stay awake” and everyone “fidgets” as they try to connect with God. These depictions of our humanness are endearing, but they become quite significant when Sterling questions if we humans are able to love life despite God’s provoking, or despite the beauty of the cosmos showing us that death “can be more lovely than to live, / that the shell of us will decorate the sky / for eons to come, and be more beautiful for it.”

By Part Five, Sterling has shown many vulnerable aspects of herself and humanity. In doing so, she builds our trust and ushers us into clearer self-perception. We delight in her poetry and her ability to evoke perplexing subjects: our love for our children, our humanness, and our future on this earth. Knowing that she has gained our trust, she lays bare her largest truths. In “Blatta, Genus, Cockroach,” she reflects on her own immaturity and likens herself to a roach that has indulged in sweets,

… I have lost my taste for rot.

I have crept like a roach in the darkness

to tell the truth, with these hideous wings,

this coward’s heart.

Far more gut-wrenching than Sterling’s self-deprecation is the fact that we assume this persona, becoming deeply ashamed at our own indulgences as individuals and as a human race. In the next poem “Succession,” she searches for reassurance, “Tell us that it will be alright. Tell us / our small lives can rearrange these / certainties.” But ultimately, she realizes the devastation we have caused, “How much we must do / before we can tell our child / that we’ve left her anything.”

Her thought cycle is completed in “Evening Prayer,” a poem that also harkens back to the first poem of the collection. Here, Sterling imagines a bountiful world after humans have left it, where nature covers the earth, “replacing pavement with fields of wildflowers….” Ultimately, Sterling ends the collection with her wishes for her daughter in “Apology After the Fire,”

I want life to bloom around her the way she blooms

and for her to know the quiet of leaves,

the hum of growing things,

these few seeds I nudge into flower as apology.

Her apology is embedded in the sense that an individual has so little power to change the course of the world, a powerlessness that has become a constant backdrop to our daily lives. We go about our days with climate change on our radios, in our gardens, and in every nook of our lives. Sterling makes clear we are united in its inescapability and in our feelings of helplessness, while also making clear that the time has come for us to acknowledge the truth, “no matter how much it hurt[s].” Above all other things, this book of poetry asks if we can wrench ourselves away from our current trajectory, if not for ourselves, then for our children. These Few Seeds is a sounding alarm, and we must not be deaf to it.

Daria Uporsky is a writer and editor for an environmental justice and social equity firm. She also occasionally contributes creative nonfiction and reviews, and is most recently published in the Rocky Mountain regional magazine Mountain Outlaw.